Society Science

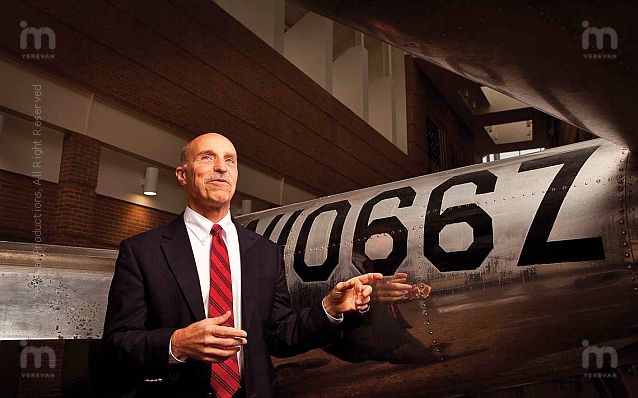

The One and Only

This is one of those rare cases when the exclusivity of an article is not confined by the interview and the story. The word “exclusive” in this case may be used in several occasions: to define a personality, a man and his actions. Yerevan Magazine is honored to introduce to its readers the exceptional nature of one man to whom even the sky is not the limit – literally.

March 13, 1989 Kennedy Space Center, Florida

NASA was getting ready for the launch of STS-29 Space Shuttle Discovery. The launch was initially scheduled for February 18, but was delayed until the month of March to eliminate the chance of potential malfunction of three main engines on the shuttle. The crew of the STS-29 Discovery was all set for the flight after having a preflight breakfast in coats and ties. This was the third mission since the tragic accident of the Space Shuttle Challenger that took the lives of its seven crew members in January of 1986. One of the astronauts of STS-29 Discovery, Dr. James Philip Bagian, was initially scheduled to be on board the ill-fated Challenger, but several months before the scheduled launch there was a change of plans and Bagian and his crew switched places in the schedule and didn’t fly. Later, Bagian would become one of the key investigators of the Challenger accident, helping during the salvage operations of the Space Shuttle crew module. Following that, he was responsible for the development and implementation of crew survival and escape equipment used on future shuttle missions. The list of Bagian’s contributions to NASA cannot be summed up in one article, yet in his interview with Yerevan Magazine, Dr. Bagian confessed that his biggest accomplishments probably came after his time as a NASA astronaut. Indeed, Dr. Bagian’s career after his retirement from NASA proves to be just as valuable and prominent.

All That It Takes

Dr. Bagian, who started his career with NASA in 1980, said as we began our conversation, “While, as a young boy, I always had wanted to be an astronaut but had put that idea aside by the time I was 12 years old as unrealistic. I didn’t think again of becoming an astronaut until I was in medical school. That was when I became aware that NASA was looking for Space Shuttle astronauts. I completed the application, sent it in, and was invited for the interview. I was ultimately selected as a mission specialist astronaut.” How simple is that! A medical student submits an application and becomes a NASA astronaut. But, in reality, Dr. James Philip Bagian was no ordinary applicant. Besides being a medical school graduate, Bagian, still in his twenties, had a pretty impressive background and work experience. After receiving a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering from Drexel University, he worked in the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School and Development Center designing ejection seats. In addition, he had experience piloting high performance jet aircrafts. “I think it was the combination of all these things that made me stand out during the interview,” was Bagian’s modest conclusion. An engineering background, experience in the aerospace industry, being a physician, and having mechanical aptitude. The list obviously clarifies what it takes to be admitted by NASA as an astronaut.

NASA

Having undergone a series of the toughest trainings in the past, the hard-to-endure challenges of the astronaut training program were nothing new to young Bagian. “To me, it was like any other training. There were no special challenges,” continued Bagian in the same casual tone, telling an absolutely non-casual story. “I happened to be a physician, but most of the things I did were engineering- related. In some missions, I was in charge of satellite launches. In other missions, I was conducting scientific and medical experiments.” In fact, mission specialists are often physicians or engineers, but Bagian carried out the duties of both. James Bagian has had two space flights. During the first flight in 1989 that lasted four days, 23 hours, and 39 minutes, the crew deployed a tracking and data relay satellite, and performed various experiments. They conducted studies on the changes of cerebral blood flow and its relationship to the Space Adaptation Syndrome (SAS) and Space Motion Sickness (SMS). SMS produces symptoms that resemble sea- sickness and affect approximately 75% of all astronauts on their first flights. In 1989, Dr. James Bagian was the first to treat SMS with the drug Phenergan by intramuscular injection. Bagian’s treatment was adopted by NASA at that time and continues to be the only treatment used as there has not been a better one developed in the last 23 years. Bagian’s second space flight took place two years later on board STS-40 Columbia in June of 1991. It was the first Space Shuttle mission dedicated to life science studies. During this mission that lasted nine days, two hours and 14 minutes, the crew performed experiments to determine how the heart, blood vessels, lungs, kidneys, and hormone-secreting glands respond to microgravity, the causes of space sickness, and changes that occur in muscles, bones, and cells in humans during space flight. That time Dr. Bagian’s exceptional skills and ability to improvise in the most challenging situations helped the crew to complete the important experiment. “We had a failure of one of the pieces of equipment that made it impossible to do one of our experiments,” Bagian recalled. “I woke up in the morning with the thought that I could fix it with the equipment that was in the medical kit: needles, syringes, etc. That was something we were never trained to do – I just improvised and it worked, so we were able to finish the experiment.” “What view impressed you most as you looked out the window of the spaceship during your first flight?” I asked Dr. Bagian. He responded, “I was amazed that even at an altitude of 185 miles, one still could make out a tremendous amount of detail. You can see runways for airports, power line towers, many streets, cargo ships. You can see more than you would think. To me, that was the thing that no photo could serve justice to.”

Like Father, Like Son

Ever since he was a child, Bagian was interested in flying. His father’s influence in that sense was immense. “My father, Philip Bagian, was a fighter pilot during WWII and had a very distinguished career,” says Bagian. “He was in the Army Air Corps in the United States, and flew P-47 Thunderbolts in combat. He had 120 missions and was awarded the Silver Star, which is the third highest medal in the country for valor; the Distinguished Flying Cross; the Soldier’s Medal; as well as multiple air medals. He is still very active.” There is an interesting story from James Bagian’s childhood that speaks for itself: “When I was eight years old, I was in the Cub Scouts and we had to put a scrapbook together about something that interested us. I had always been very interested in flying and aviation so I did one of the NASA space programs. This was before the first U.S. astronaut had flown, and I remember thinking this would be something that would be great to do.”

Lethal Game

Despite all the research and testing, launching a shuttle has always been a game of chance. Unlike airplanes, ships or automobiles, Space Shuttles cannot undergo the same number of test flights prior to going into actual operation. It has always been a potentially lethal game – a Russian roulette of sorts – since the level of risk is so much higher than virtually any other endeavor that the question is when, not if a mishap will eventually occur. The tragic Space Shuttle Challenger disaster of 1986 aroused many speculations, due to the fact that for years the U.S. government and NASA were less than forthcoming regarding certain aspects surrounding the mishap. Dr. Bagian was part of the investigation group of the fatal Challenger accident, in charge of determining what exactly happened to the crew, supervising and conducting the investigation of the cause of their death. Another dramatic aspect of the story is the fact that initially Bagian was scheduled to be on board the Challenger Shuttle on that day. Fortunately there was a change in schedule, and he and his crew did not fly that day. It is hard to imagine the feelings of a man who witnessed the tragic death of fellow crew members, realizing that he could have been one of them. Understandably, he did not provide me with much detail on this subject. But the fact that Dr. Bagian was actually the first one to make the dive and confirm the location of the remains of the Challenger crew members in the Atlantic Ocean speaks for itself. The scanty report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident stated that the crew of the shuttle died instantly as the shuttle broke apart 73 seconds after launch. But was that really the case? The investigation conducted by Bagian’s team revealed an even more sorrowful fact: the crew was not killed instantly. Astronauts on board the Space Shuttle Challenger were still strapped to their seats and were alive until the moment the shuttle hit the water. This dramatic fact was to serve as a bitter lesson for NASA because NASA had made the decision to remove the escape system that had been available on earlier Shuttle flights for crew use. “If there had been an escape system on board similar to the one that was placed into service after the Challenger mishap, there would have been a reasonable likelihood that the crew could have survived,” Bagian continues. “NASA utilized escape systems on board the shuttles starting from the first flight after the Challenger accident until the end of the shuttle program in August of 2011. I was one of the individuals responsible for that project as well. Even though we came up with the escape system, up until I flew my second flight on the STS-40 Space Shuttle Columbia in 1991, there was no official training on how to use the system for events similar to the Challenger disaster. So we trained the crews unofficially.” In 2003, Dr. Bagian was also appointed as Medical Consultant and Chief Flight Surgeon for the Columbia Accident Investigation Board. Unlike with the Challenger disaster, there was a full report done on the space shuttle Columbia accident, and Dr. Bagian’s team was allowed to publish that report. I was always curious to know why there weren’t other manned moon landings after the last landing of Apollo 17 in December of 1972. “There hasn’t been support to provide funds for manned landings on the moon,” Bagian answered. “The United States planned 25 Apollo missions. There were supposed to be eight additional landings above what actually occurred, but due to the lack of interest in funding they were canceled. That picture hasn’t changed dramatically since the 1970s. And currently there is no concrete timeline to go to the moon or Mars. Back in the 1970s it was a combination of many things that supported the program; mainly it was a competition with the Soviet Union, and that competition played a large role for the both sides. I think, once we got to the moon, the interest and then the financial support dwindled,” concluded Bagian. This is attested by the secret presidential recording from the Kennedy Library archives that only a few months ago saw public release. I found that historic conversation between President Kennedy and James Webb, the head of NASA, on the official JFK library website. The recording system was installed by Kennedy himself in order to preserve an accurate record of Presidential decision-making in his White House meetings. “I’m not that interested in space,” Kennedy tells Webb during their heated conversation. President Kennedy made it clear that the lunar program was supposed to be the only priority both for NASA as well as for the entire government, so the United States would beat the Soviet Union in the space race and prove the superiority of the American system.

Career after NASA

“After I retired in 1995, I continued to pursue other interests,” Bagian said, “In 1999 I was offered the opportunity by the Veterans Administration to start the first patient safety dedicated organization in the world. I thought this was the ideal opportunity to see whether I could be successful in introducing my knowledge and experience from other industries like engineering and aviation, into healthcare. From 1999 to 2010, I served as Chief Patient Safety Officer and Director of the Veteran Administration's National Center for Patient Safety. That was probably my most significant career, perhaps even more valuable than what I did at NASA.” Bagian confessed. “I was always amazed at the fact that many things in medicine are based on old systems. People would learn from one another rather than doing things in a systematic way, and if there were problems they would be corrected individually instead of thinking what could be done for everyone to learn from someone’s experience. A tremendous number of people are killed because of unsafe medical care. So now I was given the opportunity to form the first organization that would actually attempt to ensure safety, not just talk about it. We set up standards, tools and methodologies in countries all around the world and changed the way healthcare is delivered today. We realized that we were actually saving lives. Simply telling people to be careful was not a good strategy. There is no reason that a patient has to be hurt before one can learn something. With that in mind, within the healthcare industry we popularized the notion of reporting what are called ‘close calls.’ We have also authored many publications and had training programs for over 14 countries around the world to set up safety programs and develop tools that are used throughout the world to this day. A lot of our initial ideas were implemented in a large way across the VA system. We also changed the design of medical equipment that has been less than perfect and could harm patients. All this was done not only for our patients here in the U.S., but for all the patients around the world. I think we were very successful in our work, and this has been absolutely satisfying.” Dr. Bagian is currently the Director of the Center for Health Engineering and Patient Safety in the Department of Anesthesia at the University of Michigan and is actively involved at the national level with standard-setting organizations to make sure that what was developed in the VA can benefit others as well. In one of his keynote addresses to the physicians at Montefiore Medical Center about patient safety procedures, Bagian ended with these words, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed people can change the world.” There is definitely no doubt that Bagian with his team has proven this statement right. Dr. Bagian and his wife live in Northville, Michigan. They have two daughters and two sons. Both daughters are engineers, their oldest son is currently working as an engineer and the younger son is in engineering school. Airplanes and space shuttles are not the only adrenalin-pumping activities in Bagian’s list of interests: he is also an ardent motorcycle lover. On many occasions he prefers motorcycles to cars and often rides them to work. Dr. Bagian owns not one or two, but seven of them.

Post Scriptum

An engineer, a physician, a NASA astronaut, an Air Force-qualified freefall parachutist, a mountain rescue instructor, a private pilot, director of the Veteran Administration's National Center for Patient Safety and a professor at the University of Michigan. No, this is not an A-Z list of careers of different people. Unbelievable as it may seem these all constitute one man, who throughout his life managed to distinguish himself in various occupations and made invaluable contributions in all his endeavors. They say, the more you lose yourself in something bigger than yourself, the more energy you will have. Well, if that is the case, Dr. James Philip Bagian’s energy supply must be unlimited.